The latter is rarely a problem for molecules, but there are so many combinations of atoms

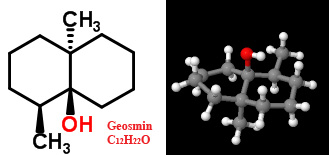

1. Geosmin and its Unsaturated Version

Fertile soil is actually a blend of living and nonliving material, so it's not surprising that the characteristic smell of freshly plowed earth is due to a compound released by bacteria. Almost 50 years ago, a mixture of compounds from a smelly strain of Streptomyces griseoluteus was obtained. Some species of Streptomyces decompose leaves and organic matter in soil and are known to produce antibiotics. The investigators tried to purify the mixture through ether-extraction and by using activated charcoal and chloroform. Although they did not reduce it to a single compound, the mixture retained its earthy odor even after it was diluted by a factor of a billion!

Two years later, after using methylene chloride-extraction and gas chromatography, another group realized that the smell did not come from what was previously believed to be a blend of esters, acids, alcohols, aldehydes and ammonia. It was mainly due to a molecule which they dubbed geosmin.

When it's too concentrated, geosmin smells like manure. But when a concentration of 0.7 micrograms per kilogram (the human nose's threshold) is not too amplified, the molecule's interaction with nasal receptors is a pleasant experience for most people. It also gives rise to the smell of soil after rainfall. When some animals are drawn to the odor of geosmin they place their snouts into the ground and help distribute bacterial spores.

When it's too concentrated, geosmin smells like manure. But when a concentration of 0.7 micrograms per kilogram (the human nose's threshold) is not too amplified, the molecule's interaction with nasal receptors is a pleasant experience for most people. It also gives rise to the smell of soil after rainfall. When some animals are drawn to the odor of geosmin they place their snouts into the ground and help distribute bacterial spores. More recently, geosmin has also been found to be released by some cyanobacteria, and the perfume industry have found geosmin in three species of cacti flowers. Discovered about 15 years ago, the unsaturated version of geosmin, dehydrogeosmin, has a musty, earthy odor and is found in over 50 members of the cactus family. It's ironic that desert plants are producing a smell that we associate with damp places.

2. Filbertones and A Related Ketone

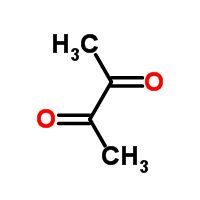

Filbertone's ketone group and part of its methylated skeleton is reminiscent of butanedione, a cheesy-smelling compound partly responsible for the flavor of butter.

The enantiomer ratio of filbertones is fairly constant and independent of the hazelnut's geographical area.

After laboriously handpicking over a thousand nuts from their socket-like receptacles and drying them for weeks in the Avellino sun, I once tried to smuggle them through the Montreal airport. They were confiscated. I hope the custom officers at least cracked their shells, bit into the kernels and released their filbertones.

- Geosmin, an Earthy-Smelling Substance Isolated from Actinomycetes http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1058374/?page=1

- The Earth's Perfume _http://web.expasy.org/spotlight/back_issues/035/

- In situ measurement of odor compound production by benthiccyanobacteria _http://pubs.rsc.org/en/Content/ArticleLanding/2010/EM/b918487b

- Filbertone: Molecule of the Month http://www.chm.bris.ac.uk/motm/filbertone/filbertoneh.htm

- Chirality and Odor Perception _http://www.leffingwell.com/chirality/filbertone.htm

- Perspectives in Flavor and Odor Research _Philip Kraft (Editor), Karl A. D. Swift (Editor)

- Molecules P.W.Atkins. W.H. Freeman. 1987

- http://www.chemspider.com/